Blog: Oral Tradition, Environmental Justice, and Emotional Relationality

Over the last few months, CULTIVATE Creative Practitioners have been developing their commissions and ideas, connecting with people across Tayside, and running workshops exploring the realities of climate injustice for local communities.

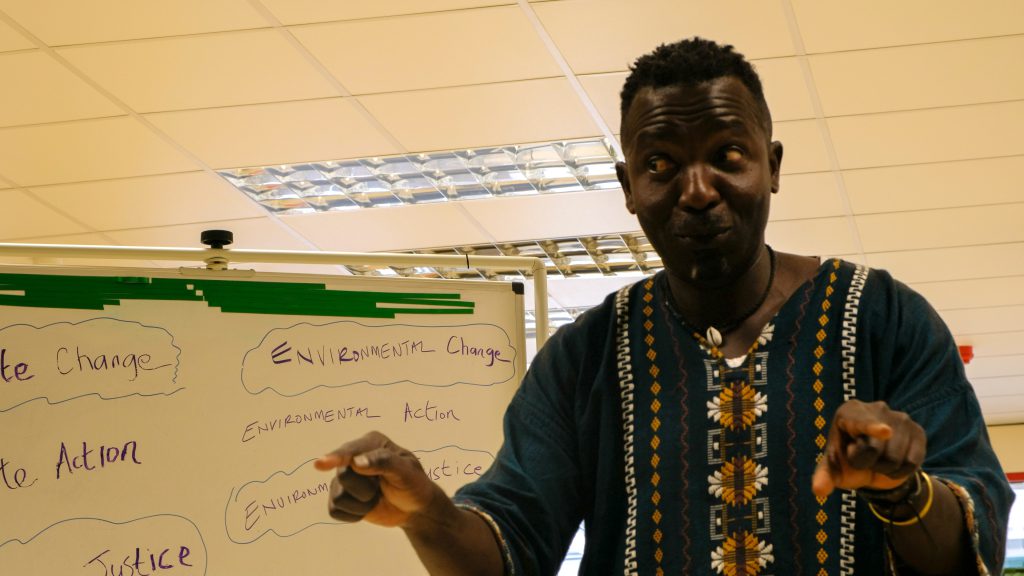

At one such workshop, storyteller, art researcher and creative practitioner Amadu Khan worked with an ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) class from various nationalities and cultures to explore their shared narratives and understandings of environmental and climate justice.

In this blog, originally published via Creative Dundee, Amadu reflects on the emotional resonance of this workshop, the unique power of storytelling across cultures, and the invaluable role of stories in environmental activism.

Preface

As an oral storyteller, I am used to a variety of emotions whilst performing! Emotional release, to borrow an African saying, is the palm oil that lubricates and embellishes the wheels of storytelling. It generates an ‘emotional relationality’ moment among the audience and between them and me. This one though was memorable.

To explain, ‘emotional relationality’ is the spontaneous release of shared feelings by performer and audience and makes them feel connected at the affective level. The emotional connectedness may be triggered by the story content, the performer’s artistry, and the appreciation of the audience.

These triggers were in play in my recent environmental-climate justice storytelling session. The setting: the Perth ESOL class of male and female parents from various nationalities and cultures – Ukrainian, Polish, Afghan, Sudanese, and Scottish. I was performing Why No One Fishes on a Friday in Mahera. It’s a popular folktale, passed through generations, in the coastal village of Mahera along the Atlantic Ocean in Sierra Leone.

Performance

‘The story I am about to tell you is about Mammy Wata, who in Sierra Leonean mythology is the God Mother of the Sea and all the flora and fauna that thrives in it’, I cued. The performance is unfolding, a realisation mirrored through the audience’s receptive eyes, ears, mouths, and silence.

‘Steeped in a curvaceous womanly figure – with angelic face, long curly hair, contoured neck, scintillating brown eyes, a coke-bottle shaped torso and lower body that tapers into a fin – Mammy Wata is the equivalent of the mermaid in many Western folklore traditions’, I paused as the European analogy struck a cross-cultural chord.

‘As God Mother, she uses her supernatural powers to regulate human conduct to care, conserve, and nourish the seas and rivers’ marine resources’, I explained.

‘So, many, many, many moons ago, the sea along the coast of Mahera is a treasure trove of fishes, with all shapes, sizes, and tastes. It is only natural for it to be a source for scrumptious meals and income, and for vocational and recreational pursuits for the Mahera people’, I paused, adding that ‘Mahera is my hometown, and indeed, its turquoise blue salty waters are equally soothing for us the inhabitants to swim and frolic as young as one can remember’.

‘Yet, as the population increases, so does overfishing and the attendant depletion of marine resources. Mammy Wata is concerned. Why can’t she be?’, I rhetorically posed.

‘She is the owner of the sea, custodian of its marine resources to whom duty of care is reposed… So, she must act!’, I re-joined.

‘Mammy Wata, therefore, ordains: “You can fish on all six days, in the night or darkness, from dawn to dusk, in the rain or sunshine, in rough and steady seas. But I command you not to fish on Fridays with immediate effect!”

‘The Town Cryer, having been delegated by the Chieftain, bellows this exhortation to the accompaniment of the ding, ding, ding tap of his goat-skin drum! He goes to every corner of Mahera – the east, west, north, and south; in the valleys, mountains, and forests; over farmlands and over the rivers, until he is sure everyone has got the message’.

‘Everyone including the mighty and powerful, rich and poor, young and old, and even the Chieftain, obeys Mammy Wata’s edict!’

‘Yet, one greedy fisherman considers the declared day of fishing Sabbath as an opportunity to make an extra penny. Sorie is his name and his notoriety for law breaking is common knowledge. The following Friday, after the first crowing of the cock, Sorie sets out to fish despite his wife pleading not to challenge Divine providence’.

‘Padam, padam, swish, swish, follows the strokes of paddling as he skims over the sea. Within seconds, Mammy Wata, by virtue of her supernatural powers, picks up the ripples. She quickly sends her guards to apprehend the culprit’.

‘That command is rapidly executed by Dragon Shirk, the lead guard!’

‘Once in custody, Sorie is duly punished! Mammy Wata turns him into a monkey’.

‘Upon return to Mahera’s shores, the Chieftain banishes him too into the forest. He isn’t allowed to live with humans anymore, for he has become a curse to the village’.

‘Henceforth, Mahera people do not fish on Fridays. And the fish and marine stock continues to thrive thereafter’, I concluded the story.

Postscript

The intention of performing this African story was threefold. Firstly, to demonstrate that oral tradition in this African culture has an environmental function – it acts a as tool for regulating conduct of duty of care and conservation for the environment and nature. Secondly, to encourage members of the audience to contribute any oral tradition from their culture that has an environmental and climate action theme. Thirdly, to facilitate a conversation around these issues. I will focus on the latter.

For one Ukrainian refugee in the audience, the African story is an allegory for the current war in Ukraine and its tragic consequences for human lives, livelihoods, and the environment. With teary eyes, she draws parallels between the story and the recent bombing of the Kakhovka Dam in Ukraine. The entire audience agree that President Putin is an incarnation of the fisherman, Sorie. Putin and Sorie’s selfish, egotistical, and reckless actions imperil human, marine, and environmental life and decorum. The audience, therefore, yearn for a past where human excesses are tamed and controlled by Divine intervention depicted in my story. They all hope and wish that through this, Putin will one day get his comeuppance.

They also yearn for this environmental injustice episode to be etched into Ukrainian folklore for future generations. It will be a ghastly tale where Putin will be cast as the loser ecoterrorist and the Ukrainian people, who bore the brunt of the dam’s destruction and its environmental injustice and ecological disaster, as heroic victims.

If anyone needs a reminder of the power of oral traditions to evoke emotional responses to humankind’s everyday reality, then my performance renders that moment. It demonstrates the emotive transformational powers of oral traditions – to connect old and contemporary socio-cultural and political exigencies across people of different ages, geographies, and cultures. Indeed, an age-old African tale has unleashed a heartrending emotional and cultural bridge among the Ukrainian, Polish, Afghan, Sudanese, and Scottish audience. It’s a palpable reminder that humanity continually faces environmental and ecological perils.

Yet, it’s one that the audience also agrees is worth defending and fighting for. My performance has breathed life into the struggles and aspirations of the Ukrainian people to get peace and environmental justice. The magical power of oral storytelling as a creative art form for environmental activism endures!

CULTIVATE is a Culture Collective leadership programme led by Creative Dundee. The programme works with local creative practitioners to place creativity at the heart of climate justice, developing action with communities across the Tay region. Discover more about CULTIVATE.